The weather in Providence, Rhode Island, on March 7th, 1948, was unusually cold. The day before had brought with it a nasty cold spell, with the low reaching a temperature of one degree Fahrenheit. Despite the cold, snow hadn’t fallen in nearly a week, leaving only a thin layer of ice to go along with the bitter freeze.

Despite the frost, in the Kinsley Park Stadium, the Chicago Stags and the Providence Steamrollers met to play a game for the Basketball Association of America, which would soon merge with its contemporary the National Basketball League, and become known as the National Basketball Association. The Stags and Steamrollers would both fold by the time the decade would finish, their organizations plagued by lack of money and fan interest. The NBA was decades from becoming the cultural mainstay it is today, and was still a few years from even drafting the first African-American player.

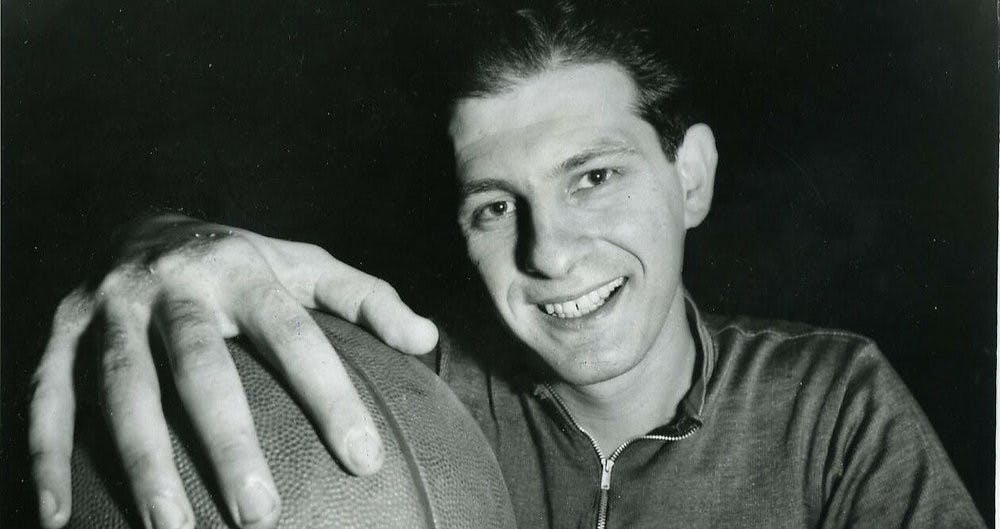

But on that cold night in Providence, Max Zaslovsky was putting on a show.

In a game that would be barely recognizable to the clean, calculated and athletic games that are played today, Zaslofsky was by far the best player on the court. He was the only player on either team to complete double-digit field goals or double-digit free throws, completing 15 and 10 respectively on his way to 40 points, a Herculean effort for the time and a career best. The next highest scorer was Kenny Sailors for the Steamrollers, who put up a respectable 19.

But what was Zaslofsky’s shooting percentage for the game? How many rebounds did Sailors put up to go with his 19 points? Sure, the Stags went on to win 89-81 because of Zaslofsky’s heroics, but what was the game flow? Was the game close in the last few minutes or was it a blowout that the Stags took their foot off the gas for?

The answer: we don’t know. We never will.

This is the curse of the earliest days of professional basketball as we know it. The audience was not nearly what it is today. Baseball, boxing, running, and even football had a much larger following at the time, and no one cared enough or had developed the game enough to care or keep track of every little statistic the way we do today. Statkeepers often kept their cards to a minimum to save money on paper, writing only the final score and the points scored by each player. Finding a stat card that kept track of assists or rebounds is like finding gold for this era.

Because of this, there are typically two players that are remembered from the 1940s: Joe Fulks, who held the record for most points scored in a game at 63 until someone named Elgin Baylor came along, and George Mikan, who started his utter dominance of the 50s a little early with some great runs in the late 40s.

Left in the dust is Max Zaslofsky. Born to Jewish Russian immigrants in 1925, Zaslovsky was a prolific high school basketball player while living in Brooklyn, being selected to the All-PSAL team. After serving in World War II in the Navy, Zaslovsky attended St. John’s University and played there for a year. After a decent freshman season in 1945-1946, he joined the BAA draft, where he was selected by the Chicago Stags.

It was during these early years with the Stags that Zaslovsky made his biggest impact on league history. In his rookie season of 1946-1947, he was named to the All-NBA 1st team, becoming the youngest player to be named to the 1st team in the league’s short history at 21 years old. His record would stand for almost 6 decades, only being broken when a young star named LeBron James finally broke it in 2005-2006.

A year later, in the 1947-1948 season that he had his 40-point game in, he led the league in scoring at 21.0 points while only being 22 years old. In doing so, he accomplished not only becoming the first guard to lead the league in scoring (and would be the only for 20 years until David Bing accomplished it in 1967-1968), but also became the youngest player as well. This particular record would last even longer than being the youngest All-NBA 1st team member, as it would last until Kevin Durant finally broke it in 2009-2010.

Even though his most notable accomplishments occurred in his early career with the Stags, his career after these impressive records was still very successful. After Chicago had to fold its team, he went on to become the first major star of the New York Knicks in their storied history. In his first two years with the team, he led them to back-to-back NBA Finals, before being defeated by the Rochester Royals in 1951 and Mikan’s Lakers in 1952, averaging a combined 17.1 points per game in the two runs. In addition to his original All-NBA 1st team honors in his rookie season, he was named to it three more times, in 1947–48, 1948–49, and 1949–50. He also became an All-Star in 1952, the second time ever the honor had been awarded. By the time he retired in 1956, he was the 3rd leading scorer in NBA history, trailing only Fulks and Mikan.

In honor of these accomplishments, the NBA decided to name Zaslovsky as a 25th Anniversary Team Nominee in 1971, a prestigious group of the pioneers of the sport. Of the 25 nominees on the list, there are two who have not been inducted into the Hall of Fame. One of them, Bob Freerick, played a total of four years in the NBA.

The other one is Max Zaslovsky.

In 2013, Bernard King was inducted into the Hall of Fame. When he did, every single scoring leader in a season in the NBA had officially been enshrined, except one.

That one is Max Zaslovsky.

Every player with three or more All-NBA 1st team selections has been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Except Max Zaslovsky.

Why is someone with as prolific a resume as he left out of the Hall of Fame? Sure, his stats don’t blow you away when you first look at them, but taken in context, he was always an above-average player. He doesn’t have an MVP to bolster his resume, but neither do many other players in this era in the Hall of Fame, where MVPs were scarce thanks to Mikan and later Wilt Chamberlain. He lacks a championship pedigree, but he was the lead player on two NBA finals teams, which must count for something.

The biggest reason Zaslovsky lacks a Hall of Fame bust: a lack of pressure to put him in. After his playing career, he was mostly out of the limelight, coaching in the ABA for the New York Nets for two disastrous seasons in 1967-1969 before resigning and going back to a quiet private life. In 1985 he would die from leukemia at only 59 years old, only furthering his descent into obscurity as the NBA began to take hold of the public eye with Magic vs. Bird and the rise of Jordan. Other older legends such as Bill Russell, Pete Maravich, and Chamberlain took advantage of this newfound public awareness to help cement their legacy by staying associated with the league, something Zaslovsky was unfortunately not around to accomplish.

Zaslovsky played in an era of basketball that was extremely different. His stats aren’t eye-popping like Chamberlain, and he doesn’t have the championship pedigree of Mikan or Russell. However, Zaslovsky is undeniably a pioneer of the game, and his records and accomplishments are proof.

That cold night in Providence was a showcase of one of the greatest basketball players of his era. The Hall of Fame should recognize him as such.